|

|

& Border Jumpers

The Story of

a Union Organizer

project support

from the

Rockefeller Foundation

Interview with Agustin Ramirez

Fairfield CA (11/21/01)

I was born in a town called Atacheo, about 16 kilometers from Zamora, Michoacan. It's a village of about 5-8000 people. I was born in March, 1956, the oldest in my family. There are three brothers, including myself, and four girls.

When I was born, we lived in Atacheo itself. I think my dad came as a bracero to the US before I was born, to the Modesto/Livingston area. After I was born he came again, in 1958, after my other sister was born also. We lived in Atacheo for a few years during this time, and then we went to live in Mexico City. In 1963, through the bracero program, my dad got a letter from his employer, permitting him to come over here and live in California.

I think he came every year as a bracero, at least until 1958 or 59. My grandfather, my father's father, did not have land. He wasn't part of an ejido, and was from another village. He married someone from Atacheo, but because she was a woman, she didn't have access to land either. So they didn't have any land that they could farm. We moved to Mexico City so my dad could look for work. He got a job in a factory where they made metal buckets. We had relatives in Mexico City, so when we moved there we moved in with them. We lived in a vecindad, just a little room where everybody shares a kitchen.

|

|

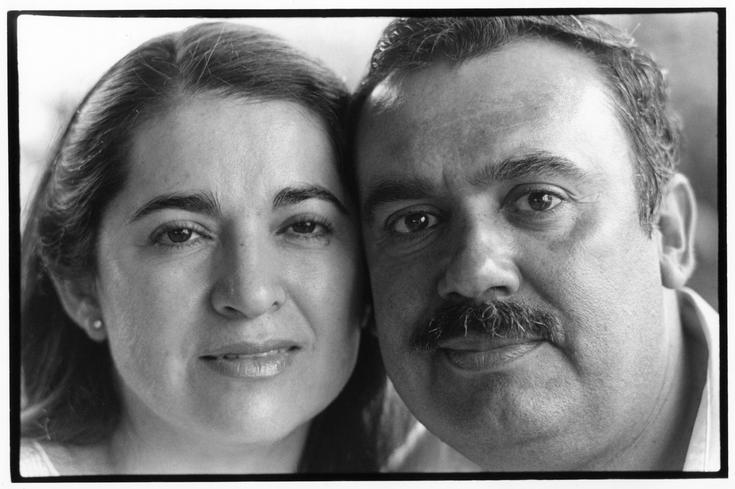

Fairfield, CA 12/3/01 Agustin and Elvia Ramirez. Agustin works as a union organizer for the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, and Elvia works in a Napa Valley winery. |

We were just there for a year and a half, and then moved back to Atacheo. My father began going to the US again as a bracero. We used to go meet him every time he came back, and he always used to bring someone to come back because they knew that all the relatives would get something. They'd always ask, "When is he coming?" When someone came back, all the relatives used to gather around. He used to bring something for as many people as he could.

In those times, people couldn't afford to buy clothes like that in stores, at least where we were. Especially the jeans. In Mexico at that time, if you were working in the fields, as a peasant in the countryside, you'd never see that kind of thing. Your pants would be made of some very inexpensive material. When ;you wore jeans or something from the US, it was like, this is it. I remember he always used to bring us these checkered shirts. When we would wear them to school, even the teacher used to say, "Your dad is here! Your dad just came home!" For two or three days, you'd be going with completely new clothes. And you could afford it if your dad was working over there.

You could tell which garments were from the US. The material was different. In those little towns, you'd normally make your own clothes. So this was something extraordinary, just having one of those little jeans jackets. For people who didn't go to the US, even though they had their own land in the village, these things weren't available or were very expensive.

The nature of the ejido was not to make a lot of profit or cash income. It was just to give people something to live on. The slogan of Zapata was the land belongs to those who work it. It was a different kind of idea. The land was to give you something to live on, not to make money out of. They started with four hectares per family, a little more than 8 acres. If you had four kids, they would have to share that, or you would apply for the extension of the ejido. Usually that would happen, so they could give the young male adults a piece of land of their own, for them to build their houses and future. It was just to live on, not to make a lot of profit.

DB: So did the ejidatarios in town after a while start thinking that they wanted to go work as braceros too?

Mostly everyone I know who came to the United States at that time were ejidatarios. During this time of the 1960s, the economy of Mexico wasn't doing great, and it got worse. And the only thing you could grow on that land was corn or beans. Our district, where I come from, did not have access to water from wells. That meant you planted corn, and waited for the water to come from the sky. If it didn't come, your corn didn't grow. If you didn't have a good season, if your crop didn't grow, you didn't have a good year. So a lot of ejidatarios opted for leasing their land over there and coming to the US to get a little money. Their intention was to use it to invest in digging a well, and then stay.

In our area, there was a big boom in tomato growing in the 1980s. A lot of tomatoes that come to the US come from the valley of Zamora. Before that, it was strawberries. But all that is recent. In the 1960s, people didn't have access to the resources to do that kind of farming. Some of the wealth that made that possible was when people came to the US, made a few dollars, and invested those dollars in machinery like tractors.

In Mexico, the land was divided between ejidos and small property-owners. The ones who are doing the modern farming in Zamora now were the property owners before. For the ejidatarios, getting the well and tractor was really more for the use just on your own four to eight hectares. At that time, you could not sell ejido land, you could just transfer it to your family, and land was very expensive. The ones who wound up doing the modern agriculture were the small property owners, the ones who were wealthy to begin with. They had the land already. I don't think they ever came as braceros.

My father came as a bracero because he did not have any land. He was one of four brothers, and his father didn't have land either. We never thought twice about going back to farm in Zamora after we came to the US because we had no land to come back to. My parents used to say that the goal for them when they came was to stay for a few years, and then go back to Mexico and start a business. Today, that's still their dream. It's just that their business is here now.

|

|

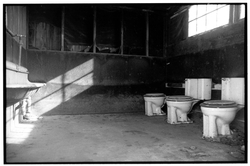

San Joaquin Delta, Stockton, CA 7/19/95 A camp used for braceros in the 1940s and 50s, and which was still used to house migrant farmworkers up until the 1980s. |

DB: So how did it come about that your family finally came to the US?

I came to the US in 1963. I was seven years old, and I don't remember which town we originally came to, but I know we lived in camps. One of my earliest memories is coming to a camp near Livingston in the Valley, and we were living by fields of figs and peaches. My dad bought this car, which we called El Perico, the Parrot, because it was a green car, I think from the early 50s. We used to enjoy going out in the night to go chase jackrabbits. My dad would take us to the fields, and then suddenly turn on the lights, and all these rabbits would start running everywhere. That used to be our thrills. We used to make houses and tunnels out of the boxes that the adults used for picking peaches. That was our playground. We didn't have slides or all those things. But it was amazing, all the families that did that. At that time it was just natural for us to go out there and help our parents picking peaches. I remember I used to make little buckets for my sisters according to their size. For the two year old, if she wanted to help, we'd make a bucket from a gallon container of milk. The bigger ones would get bigger buckets. The bigger you were, the more you could carry. We enjoyed it and we didn't think anything of it. That's just the way it was. Not just weekends, but every day.

When I came here I was seven, and at that camp where we lived for a few years, I don't really remember if we were even going to school. We were always with our parents, and the camp was surrounded by the fields, so we always knew where they were. My mom would make lunch and bring it. If we got tired working, we'd just come back to the camp. We had access to a TV, and this was something new to us. Whenever we weren't out there with them we were just plugged to the television.

Our camp consisted of individual little houses, each with one bedroom. But it was a migrant camp, surrounded by wire. There was a laundry room there. Whenever we wanted to go shopping, we'd go to the little town near it, I think Le Grand.

DB: From the way you describe it, it sounds very warm and close, like you got to be with your parents every day, and everyone was very close to each other.

Yes, if we wanted to go out there where they were working, we'd just go out there. Maybe it's just that we loved to be with our father because before he was always gone. That's probably why we loved it so much. Because we were all together. We could all go see rabbits jump or we could all go pick peaches or pick figs, or we could all go for a ride in the car, which was a treat for everybody. We'd never had a car, so at that time, it was a treat.

DB: Why did you leave the camp?

My parents bought a house at the end of 1963 or the beginning of 64, in Merced. By this time, I'd become the interpreter for my parents, and helped them buy the house. They didn't know anybody else who spoke English. You learn English when you're a young kid very very fast. You don't learn it through books, but by necessity. In order to get along and do anything, you have to learn. I was certainly no expert, but I knew more than my parents did. So everywhere they went, I was the interpreter. That's actually how I learned.

In Merced, I began going to school, and I went there until 1969. That was the year I went back to Mexico, when I was 13. I went to school in Merced through the 7th grade, and at the beginning of the 8th I left. During those years, we were to a school where they were the minority. They said they went through all these thing that we were probably doing to the white kids in our school. But even though the relationships were hard at the beginning, I think it was a good thing.

DB: Did your family stay in Merced all the time, or did you leave home sometimes to work in other places?

Every year we would follow the seasons. We would pick peaches, apricots, cherries in the San Joaquin Valley, and then we would end the season in Lakeport, near Clear Lake. We only left home, to live somewhere else, twice a year. One time would be to pick cherries, which wasn't that far, maybe three hours away. For that, my two parents and myself used to go and we'd live in the car. There was a shower there at the park, and we'd stay for two or three days, and then come back. Then we'd go back again for the other three — Thursday, Friday and Saturday.

When we went to Lakeport, that was for a month. The whole family came then. We did that from 1964 or 65 to 1981. Even after I was married, my wife came with us a couple of times.

DB: By the time you went back to Mexico after the 7th grade, you must have been pretty accustomed to life in California. Why did your parents decide to send you back?

The main reason why I went back to Mexico was the war in Vietnam. My parents didn't feel that they wanted me to go to the war. Even though I was barely 13, that was the main reason.

Being married and having kids right now, I can see how hard it was for them. I mean, I know how hard it was for me to leave, but now I'm understanding what it meant to them. They sent me over there at the age of 13 to live with relatives and in boarding houses. And I went back to Mexico by myself. They were here, and they were afraid that if I stayed here, I would have to go to the war.

DB: Why didn't they want you to go? How did they talk to you about it?

I remember them saying that the war was something that was just not right. There were a lot of young men being killed. Every day in the news you'd see a count of how many people got killed. You'd see that Hispanics and Blacks were the ones on the front lines. Their goal was still to go back to Mexico, as it still is to this date, and they've been here since 63. Their goal was even fresher at that time, when they hadn't been here so long — "We've got to get out of here. We've got to go back."

Sending me back was a first step towards achieving that goal. After I'd been there a few years, by 71, another sister came back. And a year after that, my other brother went. So at one time there were three of us in Mexico, while my parents and four other kids were here. The family was divided. It was a way of achieving their goal of going back to Mexico, and giving us an education in Mexico.

They always told us that in Mexico, if you had an education, you could live well. Because of their lack of knowledge about financial aid for school programs, they didn't know you could ask for assistance here. They just felt that a Latino working in the fields here had no future. They thought that would be our future, and they didn't want that. I remember on many occasions my father would say, "I don't want you to work like me, here in the fields."

They asked me if I wanted to go to Mexico. And at the beginning, I said, "No way." But then one year, after picking pears, my parents said, "If you're going to go this year, this is the time to go, because school is going to start over there in mid-September." So I told them I would try it for a year.

|

|

|

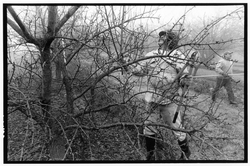

Fresno, CA 1/10/02 Joel and Abel Mendoza prune apricot trees. |

DB: How did you get there?

My mother drove me back. We went to Zamora. She had a very good friend there, and I stayed in her house for that year. I had finished 7th grade here, and when I went to Mexico, they gave me an examination to find out my abilities. Then they put me in 6th grade over there. It was essentially the same — over there grammar school stops at the 6th grade, and here it stops at the 8th, which is where I would have been. My parents put me in a Catholic school, which was the most expensive school in Zamora. It was funny. In the US, we were at the bottom because we were farm workers and we didn't have the ability to buy the best things here. Yet in Mexico, because we were farm workers here, I had the ability to go to the most expensive school in my town, where all the rich kids were. It was such a contrast. Here you see the way people look at you when you're a farm worker, you just feel it. And in Mexico, I was at the top of the line. We had a uniform, and I had to wear a suit every day with a tie and a jacket. Zamora is a very rich city, because it has a lot of agriculture. Per capita, I think it's one of the richest cities in Mexico. And here I was, going to school with some of these guys.

DB: When they asked you what your parents did, what did you tell them?

I told them they were farm workers. But at that school, they were teaching English in the 5th and 6th grades, and a lot of kids loved me, because I did their homework for English, their worst subject. The teacher who was teaching English used to pull me out and ask me questions. It's sad to say, but I didn't know Spanish that well. During those years in California, I was trying to learn English so hard that I kind of lacked in learning Spanish. At home, my mom used to say, "Hablen en ingles." Speak English, so you guys will learn faster. I know that was a mistake now, because you have to keep speaking Spanish so you won't forget it. But when I went back to Mexico, the kids used to make fun of me because of the way I spoke Spanish. It was broken Spanish. After a year or so, I got the hang of it. Still, I was welcomed with open arms. It wasn't because of who I was, but because I'd help them with their English classes.

I only went to that particular school for one year. Then I personally realized that it was not my school. Those were not my people, not the people who are going to be friends with me. They were always carrying a lot of money, and their parents had big old cars. Kids even went to school on their own motorcycles. So at the end of that year, when it was time to move on to a secondary school, I told my parents I wanted to go to the government school. Those were the kids I was going around with. I went to the Escuela Federal Secondaria Jose Palomar Esquirol.

That was the school where I met my wife Elvia. When I was in the third year of secondaria, she was in the first year.

From there I moved to Guadalajara, which is about a two-hour bus ride from Zamora. I went there because I wanted to go to the University of Guadalajara, and to attend that university, you have to attend the preparatoria [the three-year post-secondary school that precedes university] in that state. If I had stayed in Zamora, I would have had to go to the preparatoria in Morelia, which is affiliated to the University of San Nicolas Hidalgo.

I made most of these decisions myself, because my parents were here. They went to Mexico once a year, but I came to the US in December and in June. During the vacation in December, I'd help my father prune apricots and peaches and grapes. And during June, July and August I used to come and we'd work then too, picking apricots and pears. Even when I was going to school there I still used to come here and work side-by-side with them in the fields. At one point there were three of us living in Mexico, and my parents were still working in the fields here. After a while they had a catering truck too, and with those two things they were able to support us going to school over there. Then they built a house in Zamora, Michoacan, because that, too, was part of their dream. So there were three of us living in that house, and we had an aunt who would come and help us cook and clean house. Their dream was to send one of the children each year until eventually they'd have to come too because all of us would be over there. But it just didn't materialize like that. My parents soon realized that when they went over there, even though they loved it, they didn't have an income. What were they going to do? How were they going to save up a lot of money to start a business over there? Every year they'd say, "Next year we'll come." But every year they'd save up a few thousand dollars, but that money didn't go very far when they got there, with no income. They had no land, and they had no business. That's why it's become a myth now. And they realized this after three of us were already over there.

|

|

|

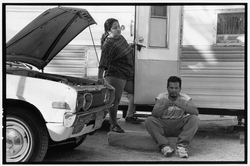

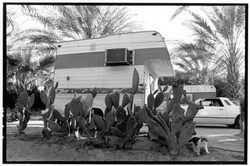

100 Palms, Coachella Valley, CA 5/15/96 Farm workers and their home in a trailer camp. |

DB: But your parents were such enterprising people, and they were able to accomplish so much. It seems hard to imagine that they simply couldn't find a way to start a business there. How much did they actually want to relocate back to Mexico?

That's the thing. Once they lived here, it was like a magnet. I tell this to everybody. It's a hard life in the US. But it's twenty times better than the life you can get in Mexico. So once my parents came here and worked hard, and they achieved what they achieved here, they were living more comfortably here. All they had to do here was sign their name and get a car or a refrigerator. They began to realize that in order to have us over there, they had to be over here to sustain it. It became a myth after a while, the idea of going back. If you ask them now, after they've been here 30 years, they'll tell you that they want to go back. For a month. Now this is where the kids are, and this is where they want to be.

Remember a few years ago, you took a family picture of us. There were 65 of us in the family then. Today, everyone in the picture is still alive, even my grandfather. And we've grown. Now there are 75 of us, I think.

I think it's true. If they'd really put their heads together, they'd have found some way to stay over there. But I think they just liked it here. Life here is a little better. Even for professionals and the middle class.

Still today in Mexico, there are houses in the village I come from that don't have running water and sewers. They all have electricity now. But things we take for granted here, in Mexico they can still be luxuries.

DB: What was the future you envisioned for yourself growing up in Mexico? Did you get what you dreamed you would?

It was a vision totally different from what I'm doing now. I planned to graduate from school. Maybe it was because I'd spent so much time outside, among plants in the fields, but I decided to study agronomy, to become an engineer. I wanted to study plants, the genetics of plants. My goal was to get that degree from the University of Guadalajara. At that time, if you had a job with the government, you had it made. And that was my dream, to get a government job. I wanted to establish myself and buy a piece of land. I wanted to farm and then open a store up selling insecticides and pesticides and fertilizers. So I went through school to achieve it.

I developed that dream because of the people I knew in Zamora and later in Guadalajara. I had an uncle, Luis Cortez, who influenced me a lot. I still love him very much. He used to work for a government agency, and he was a politician. He was a deputy in the state legislature for our district. Because the system was so corrupt, once you get an elected position, you can have a good life. Good or bad, you have a lot of power. He worked in the Secretariat of Agriculture and Cattle-raising. So he told me that I should become an agronomist, and with his friends he could easily get me a position. I liked that work, so I thought, why not? So when I came out of school with my agronomy degree five years later, he still had friends, although he no longer held an elected position. When I asked him he said, "Sure, we can get you in." In the early 80s, it didn't depend on what you knew, but who you knew. Maybe I wasn't a brilliant guy, but I knew the right people, so I got a promise of a government job.

I was in line, as you might say, when there was a big economic crisis in 1981. The value of the peso had been twelve to the dollar, and from 1981 to 1982, it went to 560 to the dollar in six months. The government not only froze jobs, but it started laying people off. My promised job just went down the drain. I would have had to wait for all the laid-off people to return to their places and then wait for my turn. That would have taken at least a few years. I could have battled it a little, but the economy was so bad. My parents didn't have any nest egg they could give me to help me start up my own business. So I decided that if I had to choose between being poor in Mexico and poor in the US, it was obvious where I should go. That's why I came back, because of that depression in Mexico. If it hadn't been for that, I would still be there. Maybe I would even be one of those corrupt guys there living on my government job.

DB: What did you do in Mexico to try to get that job?

My uncle had a friend, Guillermo Villa. He was a native of Atacheo, my home town. My parents knew him — they'd gone to school together, and called each other by their nicknames. Villa went through the ranks of the PRI and became a deputy in the Federal Chamber of Deputies. Just before Elvia and I got married, I worked with him for nine months. Over there, you have to pay your tribute to get favors. So I worked on his campaign. I was one of his aides. He surrounded himself with people — I was the agronomist, another person was a civil engineer, another was a veterinarian. Villa had only gone through primary school — sixth grade at the most. He was not a very literate person, so he surrounded himself with young people who could take care of problems. We were his group, and if he got into power, we would go with him. For a politician like him, the ones who actually do the work are his group. And when he gets elected, the people in his group get different positions in the government.

For nine months during his campaign, we would go to little towns to get the votes of the people there. People in these towns would tell him what they needed. If it was something to do with agronomy, he'd say, "Agustin, take not of that." If it was a bridge that needed to be built, he'd say the same thing to the civil engineer. He looked good because he had these engineers around him taking note of these things. Afterwards, we'd make a list of the towns and the things they needed, and it was sort of like a promise: "If you vote for me, I'll take care of it." That's how people got elected — that's the way politics worked. Sometimes we'd ride on horses for two or three hours to get to a little town of two or three hundred people. Usually one or two people living in that town would have a lot of money and influence. They might have a big cattle ranch, and could afford to give money for his campaign. So you'd have to make the trip to see them.

|

|

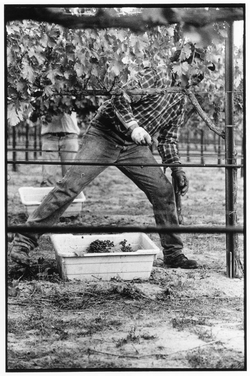

Napa Valley, CA 10/7/92 A farmworker runs down the row, slicing bunches of wine grapes from the vines as he goes, so that they fall into the plastic tub which he pushes with his foot. He works quickly because he's paid piecerate for the work. |

DB: Did your sisters and brother come back to the US with you?

My brother was only over there for two years, and then he went back. He didn't like life there, he said. My sister Patricia and I were the ones who stayed the longest. In 1981, she was going to the University of Morelia and got married, so she came back too. But her schooling there really helped her. She became a nurse and makes a good living here. In Mexico she'd been studying to become a biologist.

DB: When you came back to the US, what did you do for a living?

That was probably the hardest part of my life, both for myself and my family. My parents had put me through school in Mexico for twelve years, paying for everything I needed. All I had to do was tell them I needed money for something, and they'd send it. I lived a privileged life — I was blessed. When I was 18 my father bought me a car. Not many people had cars, and I had one. And all of that was because my father didn't want me to do the same thing he was doing here.

So when the depression came, and I told them I was coming back, they were devastated. They felt, "How could that happen?" That was the hardest thing for my parents. It was hard for me too, but I knew I'd find a way to move along. For them it was hard because everything they'd worked for seemed to be going down the drain.

I went to the University of California at Davis to see if there was a way to get credit here for my years of schooling over there, which they called revalidating my studies. But they wanted me to study two more years here, and it was so expensive that it wasn't possible. My parents offered to keep helping me go to school, and said that I could live with them. And maybe there was financial aid that I might have been able to find. But I got married that year, in 1981, and my wife was with me. I needed to do something, and I felt so bad about what I'd already done to my parents that I couldn't accept their offer. I just thought that it was an abuse to do that to them. So I told them I'd try a different way.

I ended up getting a job picking grapes in the Napa Valley, and my father was just devastated. The following year he came to work there too. So we were working in the same field, picking grapes, side by side — what he had always fought to keep from happening.

After the first season in Napa, I went back to Merced, and I was offered the job of foreman at a huge tomato ranch for $10 an hour. But my wife and I wanted to move out of my parents house. An uncle in Napa said that if we came to live in Napa we could live in a house on a grape ranch he was managing. He got us a job there.

DB: What was it about working in Napa that you liked?

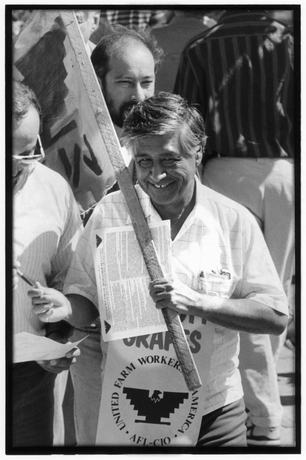

In Napa, we were making almost twice the minimum wage, because the United Farm Workers had been very successful in organizing workers there. The salaries there in the early 1980s were much higher than many other places. You could make twice the money there that you'd get in the San Joaquin Valley for doing the same job. To us, that was amazing. In Napa, we were working at a nonunion ranch, but because of the pressure of the union, the wages had gone up everywhere.

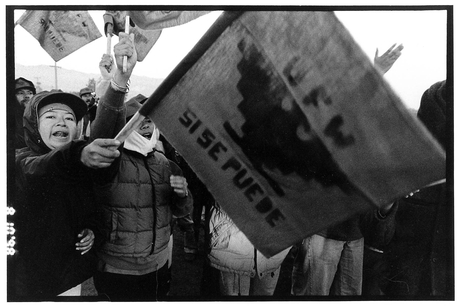

Even from the first years when my family came to Merced and Livingston in the 60s, we'd been involved with the union. My dad was a worker at Gallo, one of the original strikers in 65 or 66. He used to walk the picketline, and sometimes we'd go with him with our little flags. I was just a kid and didn't really understand, but we were part of that. Even during the times when I'd come back from Mexico on vacation, we'd go to marches.

But my parents themselves didn't stay involved in the UFW after the first strike at Gallo. They worked in the peaches and apricots and pears, and the union never organized those crops. When the second strike took place at Gallo in the late 70s, we went on the march as supporters, but they weren't strikers then. By then our link to the UFW was in Napa.

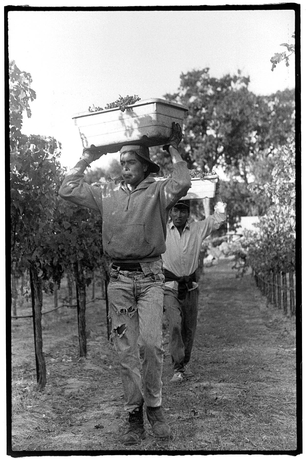

My uncles helped organize Christian Brothers in Napa Valley, and they became our link to the union. That was one of the first ranches with a union contract. We knew they were making a lot of money there, because we used to pass through Calistoga and Saint Helena every year on the way to Lakeport, and we'd stop to talk to them. They'd tell us how much they were making. It seemed very good to us, in comparison to what was being paid for the same work in Merced. It was a dramatic difference, and we could see first hand what was being done by the union. That's why I said to myself, if my destiny is to work in the fields, this is the place to do it, because this is where you can make money.

My uncles were part of the negotiating committee for the union. One of them even went to the union headquarters at La Paz to work with Cesar Chavez. He told me about sessions there in which they'd put one person in the middle of a circle, and everybody would criticize them to get them out of their senses. He said it was Cesar's way of making people able to take the criticism they'd get when they were organizers and leaders, so they'd be able to keep control of themselves. They'd say anything to the person in the middle, and they'd have to control themselves. He lasted about three or four months, but then he came back because he said it was too hard. Plus, working in the fields you'd make good money, and working for the union as an organizer you'd make nothing.

At Christian Brothers, 80-90% of the workers were from Michoacan, and about half were from my home town, Atacheo.

|

|

Napa Valley, CA 10/7/92 Two farm workers carry on their heads tubs of greapes they've picked, and runwith them to the hopper to empty them. |

DB: Did that have anything to do with how Christian Brothers got organized? Was it a movement of Atacheo people in some way?

Since they were all relatives and they knew each other, that helped them a lot. They'd grown up together, and knew they weren't going to turn their backs on each other. How could they go back to the same home town and live with each other if they'd betrayed one another?

Many of them would come back to Atacheo every year, and when I was living in Michoacan, I'd hear people speak wonders about their jobs at Christian Brothers. I wasn't really following the movement of the UFW closely then because there were other things happening in the world at that time that grabbed my attention — Chile and Nicaragua, for instance. The University of Guadalajara was sort of a socialist university, by comparison with some other schools that were more in line with the PRI. The cause of the UFW was mentioned there, but it wasn't something a lot of people followed.

I knew about it because of my family, and the get togethers we'd have when I'd come back on vacation. I remember going to the funeral of Rufino Contreras, who was murdered during a union election. They took his casket from place to place, and in Livingston they kept it surrounded by guards and two German Shepherds. They were Cesar's dogs — Boycott and Huelga, Boycott and Strike. When people would talk to me about Cesar Chavez, I imagined him as a big guy who could do a lot of things, beat up all his enemies. When I finally met him, and saw he was just a little old man, a thin guy, I was amazed.

DB: It sounds from your description that the union got really good contracts for workers, but the companies where they got them don't exist anymore. Did growers just get rid of the union eventually, or did the union also do things that contributed to the disappearance of those companies?

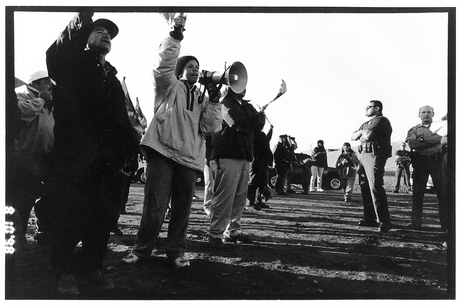

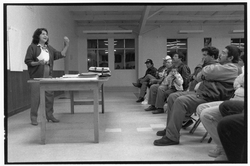

One year, just before I became the president of the union committee at Christian Brothers, they were negotiating a new contract. Dolores Huerta, who was negotiating with the company, told the workers that if the company didn't agree, they should put union flags on the tractors and drive through the streets of Saint Helena to the Christian Brothers monastery. That would have been a really big deal. Then, just as we were all on the tractors, ready to get on the freeway, we got another call that the contract had been signed. Dolores was really a gutsy person. She would be ready to take action right to the end. She was not afraid to do these things. Cesar himself would say, "Do what you have to do, and deal with the lawyers later."

That militancy was a big part of how the union won those contracts, and why they paid so well. Just an example was the money you could make during the pruning. When the union was the strongest, they were making 65¢/vine, pruning 3-400 vines in a day. Some people could make $250 in a single day They were so militant they could get whatever they wanted. But in a way, it was no wonder those companies couldn't survive.

One of the reasons why the union lost many contracts in the late 70s and early 80s, I believe, was because people got too militant. Sometimes they acted as though they'd become the owners of the ranch. Mostly it was they way they restricted supervisors. They wrote into their contract that a supervisor couldn't go into the rows of grape vines more than 10 vines. If you were further inside, you could be asleep and he still couldn't go in any farther to warn you. A supervisor couldn't tell you to go back to work after your 15-minute break, because he didn't know what time you'd stopped. Things like that were just nonsense.

DB: Maybe it was a little exaggerated in a way, but where did the sense that workers had of their rights — that they could limit the supervisors like that — come from?

I think it was partly due to the organizers. The union had some really good ones. And at the ranches they found some militant people, people eager to get some rights. People who worked in the fields never had any rights. When someone came and said, "You do have rights," it was what they were waiting to hear. When people who never had anything suddenly had power, realized that they could do something, they took it as far as they could. To the limit.

I don't really think it had much to do with their culture, or what they were taught in school. Most of these people hadn't been to school. I don't think people here acted the way they did because they had some socialist or revolutionary sense. I think it was the great work of the organizers the union had at that time, and that people were eager to find some source of justice, of rights.

DB: What about Zapata's idea that the land belongs to those who work it? Didn't that influence people?

The majority of people that came here who had land, the ejidatarios, went back after they'd been here a few years and made some money. The ones who stayed here are the ones who didn't have anything to go back to. Prior to those who came as a result of the devaluation in the early 80s, the big flow of people who came to the US was made up of those who really could not find anything else to live on, and didn't have much education.

After 1981, I think the flow of people was totally different. When I came, hundreds of thousands of professionals did also. Doctors with whom I'd gone to school were here, and dentists and engineers too. You found them working on assembly lines, or in the fields, or wherever they could find work. They had to get jobs. That's why I was here. I even had an advantage over them because I knew English. These professionals had degrees, but they just spoke Spanish. So they just had to take whatever jobs they could find.

DB: How did you become an organizer for the union?

I started pruning at Christian Brothers in late 1982. It wasn't hard work, but I didn't know how to do it, and it was embarrassing. People would ask me about myself, and I'd tell them I was an engineer of agronomy. But in Michoacan and Guadalajara, we were surrounded by grain. We knew how to fertilize corn or wheat, but we never saw a vine. So the workers would say, "Here's an engineer, and he doesn't know how to prune a damn vine." That first day of work there had a big emotional impact. I saw a lot of people I knew from Atacheo. When I would see them there during the Christmas season, they'd greet me very respectfully, saying "How are you doing, ingeniero (engineer)? Your parents are really taking care of you. You're going to make them proud."

The first day I went to work, side by side with the same people, they'd just look at me. They didn't say anything. They didn't know what to say. It was hard. But some would joke around about it. And that was their way to kind of ease the situation.

Later that year, during the picking season, the contract was up. The union needed someone to explain the contract to the people. Ben Maddox had been the negotiator for the UFW, and one of the workers told him that I knew English, and that he should ask me to read the contract and explain it. So I got a copy of the contract and did that. Then Cesar came for a march to celebrate the new contract, and he asked me to translate some things. He asked me why I knew both English and Spanish, and when I told him, he asked me to come aboard. That first time I told him no. I kept on working until 1983, and the workers elected me president of the ranch committee. When the contact came up again, I was at the table as a negotiator. And when Ben and Cesar asked me again to come join them, I said OK.

It was still Elvia and my dream to work in the US, make some money, and go back to Mexico. The first year we worked here, we saved our money, and went back and bought some land to build a house. The next year, we told ourselves, we have a place for a house, and now we need a business. We decided on pigs. My father-in-law gave us a piece of land, and we built sheds for raising them. The third year, when we went back during the winter of 83-84, bought a mill for grinding feed and a pump for a well. Then my son Edgar was born the next year, and we couldn't go. The year after that we couldn't go either. Finally we realized that were weren't going to go back. All that plan, and what we'd put into it, was gone.

And during that time, I started with the union. I remember that first day in January, Ben came to me and said, "Congratulations. You're now working for the UFW." I was expecting some training, but he gave me a set of keys and some contracts and said, "You're on your own." That was my introduction, although later I did get some training in La Paz. But I wasn't hired because I knew a lot. I was hired because I knew Spanish and English.

|

|

Chualar, CA 8/10/98 Strikers at D'Arrigo Brothers produce company call out to strikebreakers working in the fields to stop work and join the strike, as sheriffs deputies look on. |

DB: Knowing what the union pays, your income must have gone down quite a bit.

My income working in the fields was actually pretty good, although that really only means pretty good for a farm worker. I think they told me I'd be getting $1000 a month. They said, give us bills that equal that, and they'd pay them. I was supposed to give them my rent, my car payment, my electricity, and so on. They paid them directly. All I saw for the next few years was $69 a week for expenses. When Edgar was born, I had to go apply for welfare, so that I could pay for the hospital. Because I was working for the UFW, I wasn't covered by the union medical plan any longer, which was just for workers under contract. That's one of the things I really didn't like.

But I stuck with it. I thought that was the place where I could help people. I saw those beautiful contracts, but I also saw that the union was going down. I thought that if I was part of that, I could help. I really needed to help people, because so many people had helped me. In Mexico, when I was by myself, I had a lot of help from people. Good people, that I looked up to. I just felt I could do something.

I think my parents had a lot to do with that. I never had a chance to repay everything that they did for me. I couldn't do what I wanted for them, so maybe I just needed to give something to someone. That was my way of doing something for people. And I also felt that was the right thing to do. When I was in the University of Guadalajara I was fascinated by Chile. In those days, Castro used to go to Mexico every two years to give speeches, and I was fascinated by that too. There used to be busses full of us to go hear him. There were tons of people and he was really far away, just a tiny figure, but with the loudspeakers you could hear him. I saw Allende and touched his hand. That was my sense of life. What they believed and what they thought meant a lot to me. So I thought doing this work with the UFW was a way of achieving something of that dream in a micro way.

I felt that dream was to get a little piece of security, of the so-called American dream, in the pockets of people who didn't have it and would never get it. By having a union contract that guaranteed them their pay for three years, that they weren't going to get fired. People who started with those contracts in the 1980s now have their own homes. Why was that? Because they had those contracts. I'm very grateful to Cesar and the movement he organized here in the Napa Valley because they did that. If it hadn't been for that, a lot of farm workers wouldn't have the security they have right now. Even though the contracts are gone now, people were able to achieve something.

So I wanted to be part of that, and I was until Elvia said, "You better go get a job that pays," because Lisette was born. She was born in 1989. By those years the UFW was having a lot of internal problems. I remember discussing at a lot of meetings the lack of support for organizing. Everything was going to the boycott. The ones who were trying to administer the existing contracts were going through hell. We didn't have any support. Our only weapon at that time was threatening that Cesar or Dolores would come and organize a march. We knew that whenever they did that we'd get publicity and support from the community, and that way achieve some specific goal. But that was it. We didn't have funds for arbitration. When there were violations, we'd send recommendations for arbitration to La Paz, but we never got any reply. There was no money for organizing. So every year, people were disbelieving in those contracts. Still, what was left was ten times better than what else was out there. People hung on and tried to keep what they had.

Meanwhile, organizers were leaving the union. Even though they'd increased the pay from $1000 to $1500, when I had my daughter in 1989, they told me again to go to get welfare. Welfare told me that I had a full time job, and I'd have to pay the hospital bills myself. I met another organizer, who'd been organizing a tannery in Napa, and was moving to Los Angeles. He asked me if I wanted to take his place, and when he told me how much his union paid, I was floored. To me, it was a big jump, just going from the UFW to a union where I'd receive an actual paycheck. So I told him yes.

DB: You've been working as a union organizer for other unions ever since then. Why do you keep doing this work? What happened to that other dream of going back to Zamora?

Well, we still were trying to find a way of going back until my son Edgar was four or five years old. My wife and I would still discuss whether we wanted to raise a family here or go the Mexico and try to get a job as an engineer. My wife had been a secretary there, doing bookkeeping for Coca-Cola, so if we had gone back at that time we could have found something. But we realized that all our family was here. And the ties between family, not just for us but for 99% of Hispanic families, are very, very strong. In our family in particular, and for Elvia's family as well, there are four or five time a year we get together. It doesn't matter where we are, we all gather together in my parents' house, for Christmas, Thanksgiving, and Easter. We used to do it for Fourth of July, but not so much anymore, because the kids are growing up and they want to do other things.

Everybody's here. We feel that the life we have here, even though it's not a life of excessive comfort, is one we couldn't have in Mexico. You get up and have to go to work, it's true. But you have something in the refrigerator, that is also true. My wife says, "We're living from paycheck to paycheck." That's like most middle-income families live in the US. We just adjust to that. But there are other benefits as well. My wife got injured, and she's getting Workers' Compensation payments. In Mexico they don't have Workers' Comp. These benefits come from your paycheck, because you work, it's true. But in Mexico you don't have them. So for me the security net is better here than there.

One of my uncles graduated as a civil engineer in 1982, but now, 20 years later, he's just getting his break now. He's getting a contract to build houses for the Mexican Institute for Social Security, and if you get one of those contracts, that's it. But it's taken him 20 years.

I have a friend I went to school with. He was persistent, staying there even through the devaluation. He finally got a job with a Japanese company in Irapuato, who made him a manager right away because he speaks English. And they began paying him in dollars and sent him to Japan to learn Japanese. Now he has a beautiful mansion and lives like a king. He stayed there and waited for the opportunity to come. If I had done that, probably my opportunity would have come too, because the road was paved already. But we decided not to do that, and now we're here. That dream of going back over there is just that. We made our decision in 1981, and we have to build on it.

When my wife and I came here, we only had two suitcases. We landed at my mother's house, and we had a room there. Then we moved to my uncle's house, and I remember we were sleeping on the couch. We didn't have anything. When we got our first jobs, we rented an apartment and bought our first car. Now we have a house, a car, we have our kids in school. We have jobs. I think we're happy. We're blessed. And the best thing of it is that I love what I do. Elvia doesn't like what she does. She tells me she works ten times as hard as I do, on an assembly line in a winery.

I love what I do because I get to meet so many people. The best part is when you see someone who didn't realize they had the spark in them get up and say, "This is wrong. I won't stand for this." When you see a person change from thinking they can't do anything to standing up for their rights, which is such a radical change, I realize that what I'm doing is worth it.

Obviously the people who pay us don't think that way. They think the numbers are what they need. But I think an organizer's job is to get a group of people to stand up for their rights, even if they're not contributing to the union with dues. Obviously, that's the goal, but if it takes a while, that's life. Ultimately, people will be attracted by seeing that example, and to the union that's out there standing up for people. If you can get one person out of a hundred you touch to do that, you can say you did something good for that person.

|

|

Chualar, CA 8/10/98 Strikers at the D'Arrigo Brothers produce company stop a bus going into the fields carrying strikebreakers early in the morning during the strike. |

DB: How comfortable do you feel living in the US as an immigrant?

Obviously our society is lopsided, not what it should be. After September 11th, I told my wife I thought everything we've been doing for immigrant rights would be pushed back ten years. It's too early to say still, but it looks like all the talks about immigration reform are delayed. Immigrants are seen as a threat. Look at me — dark skin. Maybe I look like an Arab. And the fear people have of Arabs doesn't just affect them, but all immigrants. I'm really afraid we're going to face a backlash against immigrants as a whole. Now Filipinos in the airports are being laid off because they're not citizens. Is that fair for them? To say they have no allegiance to this country because they weren't born here? I think that's wrong. Look at Timothy McVeigh. He was a hard-core American.

I believe society as a whole has to look at immigration as a necessity, instead of putting as many walls up as they can. This country needs immigrants here to keep the wheels turning. It's filled with immigrants. But people need to come here knowing they're not going to be exploited. People have to be given rights. It should be natural. We shouldn't need a Cesar Chavez to stand up and fight for this. Obviously we're not there, but that's what I hope for some day. That people will automatically be given their rights without having to fight like this. People should have the right to organize, to join a union. It should be automatic, but it isn't going to happen right now.

|

|

Delano, CA 3/1/95 Dolores Huerta, vice-president of the United Farm Workers, explains the progress of contract negotiations to workers from the world's largest rose grower, Bear Creek Production Co., at a meeting at the union's old headquarters, The Forty Acres in Delano. |

DB: What relationship do you think your children and grandchildren are going to have with Mexico and Atacheo?

It depends on the parents. Right now, even though we don't have those really tight ties anymore, we tell our children, that's where we came from. They need to have knowledge of that. To them, the relationship is that Atacheo is the town their parents are from. We want them to know the roots of the family are there, and we've been able to achieve that.

When we went the first time with them, they liked it. Then we went two years ago and they loved it. Now my son Edgar, who's 17, says he wants to go to Mexico to spend a couple of weeks. Over there, during December, there are no limits. Here he has to be home by a certain time every night. Over there, things are booming until one or two every morning. It's just so full of energy. So that's one reason why he wants to go.

But we don't ever expect them to move back there. None of my sisters or brothers would ever think of moving back there. Three brothers were born here. They grew up here, and their children were born here. This is our land, this is where we're going to die and be buried. Our roots are in Mexico and Atacheo, but the way I see it, it's like in agronomy. When you transplant a plant, and you treat it right, it's going to grow roots. That's what happened to us. We were transplanted. Our roots are over there, but the tree that grew up is over here. And my kids' roots are here now. This is where they're going to grow, where they're going to flourish.

|

|

Delano, CA 3/31/93 Mourners carry the coffin of Cesar Chavez, founder of the United Farm Workers, through the streets of Delano, where the union was born. |

DB: How do you measure the value of your own life?

I measure it by my wife and my kids. My family. I think my most valued possession is my family, including brothers, sisters, uncles, everyone. We're very close. If something happens to any of us we're always there. That's what counts. That's what helps us get through things. That's why we're all here and why nobody's going back.

|

|

San Francisco, 8/22/88 Cesar Chavez, on a picketline in front of the Mission St. Safeway, boycotting grapes. |

- Braceros & Border Jumpers

- The Story of a Bracero

- Two Braceros

- The Story of a Union Organizer

- In the Mexican Desert, a Sanctuary for Border-Crossers

WORKPLACE | STRIKES | PORTRAITS | FARMWORKERS | UNIONS | STUDENTS

Special Project: TRANSNATIONAL WORKING COMMUNITIES

HOME | NEWS | STORIES | PHOTOGRAPHS | LINKS

photographs and stories by David Bacon © 1990-

website by DigIt Designs © 1999-