|

|

Trincheras

A Descendent of

Joaquin Murrieta

project support

from the

Rockefeller Foundation

Interview with Antonio Rivera Murrieta

Phoenix AZ (12/15/01)

DB: Where are you from?

My name is Antonio Rivera Murrieta. I was born on February 19th at a very beautiful place in the state of Sonora- in Trincheras, on the land of Joaquin Murrieta. I calle it Joaquin Murrieta's land because that's what my great grandfather told me and he was Murrieta's cousin.

DB: What did they say to you in your youth about Joaquin Murrieta?

They spoke about him as the one who went to California at the time to guide the others from Sonora, to mine gold there. There used to be 10,300 people living in California who were from Sonora back then. After they returned to Mexico, they were afraid because of the persecution against Murrieta, and they didn't speak much about him. That was very true of my grandfather, although not my great grandfather.

|

|

Phoenix, AZ 12/9/02 Antonio Rivera Murrieta is the president of the association of descendents of Joaquin Murrieta. He lives part of the time in Phoenix, where he works in a warehouse, and part of the time in Caborca, Sonora. |

They feared that the people who persecuted Murrieta would follow them all the way to Trincheras. In addition, people from our family, the Murrietas, couldn't come to the United States - it was taboo. Many would be denied entry, many were denied a passport and others were denied entrance. One of them was Juan Murrieta- brother of the president of the association of Murrieta's descendants in Trincheras. It took the US government more than 3 years to give me a visa because they'd ask me if I was in the Communist Party, or if I was an activist against the Mexican government. They made a lot of excuses, but I knew what the problem was. It was that I had the last name of Murrieta. The name bothered them. So it took 3 years. I had an appointment every 6 months and finally after 3 years they gave me my passport in Sonoita, Sonora.

DB: What happened with Juan Murrieta?

Juan Murrieta was passing through Nogales and they said they asked him, "are you related to Joaquin Murrieta?" When he answered that he was, they told him that he no longer had a passport, and they ripped it up. This happened in 1946 -47.

DB: So almost 100 years after Joaquin Murrieta died, they still feared him?

They still had that fear because the textbooks in the primary schools in Arizona and California said he was a "gringo eater," that he killed one for breakfast, one for lunch and another for dinner. They said he killed people in knife fights, and called him a bandit, an assailant. But we all know that Joaquin Murrieta was a social fighter. He wanted to retrieve the part of Mexico that was lost at that time in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

DB: When I was a child I read the kinds of things you're talking about in the schools I attended in California. What was the real story of Joaquin Murrieta? Where was he from and what did he do?

The true story is that the people from Sonora living in California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas — the Mexicans here — were the last ones to realize that the land wasn't part of Mexico any more, and that they were no longer Mexicans. There wasn't mail in those days, or anything that could have told them that this happened. They started to realize it when Anglos came and wanted to take away their mines, their farms, their cattle, their way of living and the little they had. In addition, they were assaulted in Yuma.

There were many Joaquin Murrietas. Many Mexicans were angry during that time and fought, but Joaquin Murrieta lasted the longest because he had more luck and was more organized.

He wanted to recover that part of Mexico that was ours. There is talk that he had contact with the Mexican federal government back then, but the federal government didn't support his effort to recover that lost part of Mexico. So the only thing left for him was to defend himself and the rights of the Mexicans — the people from Sonora who were still living there.

|

|

Trincheras, Sonora 12/4/02 Alberto Murrieta, 92 years old, is the oldest living descendent of Joaquin Murrieta. He lives by himself on a ranch outside Trincheras. |

DB: Who were these people?

They were country people. They were the ones who showed the Anglos how to mine the gold, to extract the gold from the earth. Up until then, in the United States there weren't many gold mines, only one in North Carolina. So the Anglos who arrived in California didn't know how to mine the gold. It was the people from Sonora who showed them.

That's what we want to explain, so that North Americans understand the fundamental value that Mexicans made to the development of California and what it is today. That's the point. The gold fever was the foundation that made California, and people from Sonora had the principal role in teaching the Anglos how to mine the gold. Joaquin Murrieta was not a bandit. He was not a killer of North Americans. He was a social fighter, and that's why Mexicans called him a patriot.

DB: And now, 150 years later, why is Joaquin Murrieta's life still something important or relevant?

I would like North Americans to better understand us, the Mexicans — the fundamental value that we have — because we still come to work here. We come to develop this country. They, of course, pay us, thank God, but we are a very important part of this country. Chicanos and Mexicans still come to work in industry, the restaurants, the cleaning, in the warehouses, and the fields. Without Mexicans, the crops wouldn't be harvested, because, lets be honest, the majority of the North Americans don't want to work as farmworkers because it's hard work. We do. Why? Possibly because we're already used to hard work. That's what we want them to learn. And we need to learn more about North Americans as well.

DB: When did you get interested in social movements, and when did it become part of your own life?

I began to participate in forming the social movement of the International Association of the Descendents of Joaquin Murrieta in 1987. Before that, we would had conversations with Alfredo Figueroa in Blythe, California, who is the president of the association. But in 1988, we started to openly fight to clear Joaquin Murrieta's name, and for these ideas of social justice. We fight for our people here that can't get a drivers license, and whose car insurance costs them triple that of a resident or a North American. Just because someone is an illegal, it doesn't mean that he doesn't know how to drive.

DB: So the Association of the Descendents of Joaquin Murrieta is part of a broader movement for the civil rights of the undocumented here?

We want mutual understanding between the North Americans and the Mexicans of who Murrieta was, to dissipate from the minds of children and adults of that Murrieta was a "gringo killer" — that he was bandit, a pistolero, that he stole and murdered. We want people to understand that he fought to recover part of his fatherland and that he defended the Mexicans of that time.

To us, that's part of a better understanding between North Americans and Mexicans that since we're here, we have to fight for the undocumented as well , against the abuse they suffer. We have more than 3 million undocumented right now in the United States and we have no way to document them. We want an agreement that these people have rights, that they get paid better, that they can get a green card, a driver's license, car insurance, and a house to live in.

Since we started, we've helped the clinic in Trincheras, where Joaquin Murrieta lived. We have taken them medication and medical instruments, and an ambulance. We are in the process of getting them a school bus and a few other things: clothes, typewriters. We have two complete computers with printers for the high school in Trincheras. We still don't have the 23 kilometers that are needed of asphalt, to pave the primary road to the state highway.

|

|

Trincheras, Sonora 12/4/02 Filomeno Murrieta, a descendent of Joaquin Murrieta, lives with his wife in Trincheras, and ranches and mines gold as a gambosino in the surrounding countryside. |

DB: Hector Moroyoqui, the high school teacher in Trincheras, says cultural activities are needed to encourage more respect toward the indigenous heritage of the people that live there, from the Mayos, the Yaquis, the Papagos, and other indigenous groups. Is the Murieta Assoiciation also supporting this effort?

Yes, we have always been in contact with the indigenous groups. The governor of the Papagos, Rafael Garcia-Valencia is a consultant to us. He is an assistant to the mayor of Caborca, and is a teacher in Quitovac, near Sonoita, an indigenous Papago community. Because of the current change in the political party of the president of the republic, we feel that indigenous people have more support. So we're going to take advantage of that opportunity for us to ask more from the government.

The municipal president of Trincheras is of Mayo origin, from Navojoa. He helped us get into contact with the Mayo, and for the first time, three and a half years ago, we were able to bring a strong group of the Mayo to dance at our fiesta. A Yaqui group also came from Ciudad Obregon.

|

|

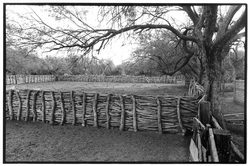

Trincheras, Sonora 12/4/02 The corral at the ranch of Alberto Murrieta, the oldest living descendent of Joaquin Murrieta, outside Trincheras. |

|

|

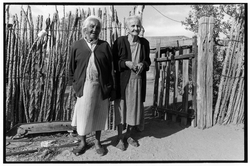

La Cienega, Sonora 12/5/02 Maria Martinez and Carmen Leon at the gate into their yard, in La Cienega. Up until the 1930s La Cienega was a center of gold mining, and had sometimes thousands of working claims. Today only a handful of inhabitants remain -- mostly the very old and very young. The rest have gone to Caborca, or to the US. |

|

|

La Cienega, Sonora 12/5/02 The hands of Maria Martinez show the effects of arthritis and a lifetime of work taking care of a rural household and family. |

DB: So the association has two areas of emphasis, one to establish this dialog between the Mexicans and North Americans to have more respect towards the Mexicans and also to have more recognition of the indigenous heritage of the people in Sonora in the area of Trincheras and Caborca?

Yes, that's it. We are doing both things — supporting the indigenous people, the Mexican Indians: the Otum, the Guarillios, the Papago, the Mayo, the Yaqui, the Cucapaz, the Mujavi, the Chimahuevo, because those are the people of Murrieta. Back then, Joaquin Murrieta was guided by them. He wasn't born familiar with the trails where they walked from Trincheras to California. That was a 6 month trip. He was guided by the Papagos, in the Trincheras region of Caborca. The Papagos and the Pimas and the Opotas, were the ones who guided Murrieta all the way to California. The authentic paths are still there — the "Devil's Path," where Murrieta passed.

Thirty years ago, on a mountain near Caborca, I saw a rock with Joaquin Murrieta's name on it, that says 1850 with a arrow next to it, next to the Devil's Path. But we have not been able to find that rock again. It disappeared as though through an act of magic. We are still looking for it.

I think Murrieta himself also had indigenous blood because his last name was Orozco from his mother's side, and that name is associated with the Otum and Pima. Even more, he could have Mayo blood, because the original Murrietas, Joaquin's parents and uncles, came from Alamo, Sonora. Alamo was the Mayos' fundamental area then. So I think that the principal blood that we, the Murrietas have, is Mayo blood.

DB: Many things remaining from that era are disappearing. I saw and photographed some of the iron crosses on the graves in the cemetery in La Cienega, that were made in the time of Murrieta, but many of them have now disappeared.

Yes. La Cienega is the place where Joaquin Murrieta had his ranch, where he kept almost 2,000 horses. It was called La Verruga. That's where he stored the horses, weapons, and ammunition he planned to use to take the part of Mexico back that was taken from us, supposedly sold by Antonio Lopez Santana after the war in Texas.

DB: What happened in your own life that made you want to get involved in the association?

Well, I have always been social fighter. I participated in politics in Mexico for many years, first in the PRI, the governing party that has just been voted out of power. I participated there for 16 years, from the time I was 16 years old. I was the President of the PRI in Caborca, and the Secretary of the Municipial President. I was the secretary for civic participation in Benjamin Hill in Sonora. After, I began fighting against the government, and I became active in the National Action Party.

The government did not want to accept change, to support social struggles. All of the government bodies that were able to get power only used it to fill their pockets, while the town they were governing was marginalized. Apparently, they'd do work. They'd say they wanted social infrastructure to support the country people. But they would only steal from the agricultural workers, the country people. They'd tell them, you're going to plant a certain variety of peaches, for example, even though it was designed for a climate like Kentucky. How was that going to grow in Caborca? Or a grape variety that grows well in northern Italy, but cannot function in the desert here. They country people to take the loans for this, even though they were never going to be able to pay, because they were never going to produce.

So I changed parties. I started the National Action Party in Sonora because that was the only option at the time that fought against the government. The other parties, like PPS, were the servants of the PRI, they were part of them. And because of that I came as a bracero in 1985- 1985 to California. The government was after me.

|

|

El Voludo, Sonora 12/5/02 A wrought-iron headstone marks the grave of a gambosino — a placer gold miner — in El Voludo, probably from the 1920s. |

DB: When you say as a bracero — are you saying without papers? Because in 1985 the program did not exist any longer.

Yes, undocumented. I mean I came to work illegally in California because the government was following me. I went on a hunger strike of 9 days in Caborca, because my election was stolen. I ran for deputy and it was totally stolen. There were 8,000 votes against 4,000. Two days after the hunger strike, on the 20 of June of 1985, we were beaten with sticks by the state police and the Caborca's municipal police. They left me with 2 broken ribs and my forehead lacerated. One of my brothers was beaten, and many others as well.

That's why I came to the United States, because I couldn't stay over there. The government was always setting traps for me.

|

|

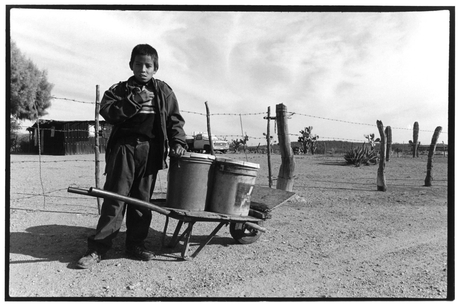

La Cienega, Sonora 12/5/02 Heriberto in front of his house in La Cienega. Today only a handful of people live in this town — mostly the very old and very young. The rest have gone to Caborca, or to the US. |

DB: What did you do when you got here?

I went to work in agriculture in California. I worked as a tractor driver for a few years, in Ripon, Manteca, Stockton, Lodi, Modesto, and Turlock. I lived in Manteca and Escalon — Joaquin Murrieta's area in the San Joaquin Valley. It should be called Joaquin's Valley, not San Joaquin Valley, because there, at the foot of Yosemite is Sonora, a town founded by the people of Sonora back then. There are still people working the gold there after 150 years.

|

|

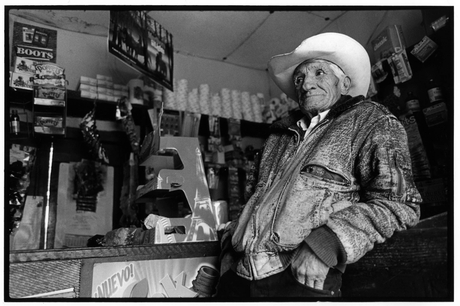

Trincheras, Sonora 12/4/02 Jesus Heberto Bejerano Vingochea, in the grocery store in Trincheras. |

DB: Do you still maintainMexican citizenship?

I am a permanent resident of the United States, but I still continue being Mexican. I'm thinking about becoming a North American citizen because now I have the option to hold dual citizenship. I still have my residence in Caborca, Sonora, and I consider myself Mexican. I was born Mexican and I'm working here because that what suits me now. But I plan to participate in politics here when I become a citizen to help my my people.

|

|

La Cienega, Sonora 12/5/02 The main road passes through the few remaining houses in La Cienega. |

DB: So you are a trans-national person, a person with roots on both sides.

I am transnational, like you are saying. I have both roots. I have learned to care a lot about North Americans, to love this town [Phoenix] because it is a fighting and working town, with all of its vices. There are rules that don't sit well with us, and racism is deeply rooted here. I worked in Minnesota, and I'll tell you frankly, there is more racism in Arizona than in Minnesota. But I want people here to understand that we did not come here to take. We came to contribute the little that we have and that we know, so that this country functions, so that it develops.

My wife's mother was born in Ireland, but came to Kansas City, Missouri when my wife was 2. So, my wife has completely Anglo roots, so that is why I have those roots too. But my grandmother was Opata, 100% Mexican, and my father was a Mexican from Paral, Chihuahua, Pancho Villa's land. Those are the strong roots, from both countries. My wife is Mexican, not even a permanent resident, because her mother never wanted any of her children to take U.S. citizenship. Not one of them, not even her daughters. They always lived in Canada, in Nacozari and in Pitiquito. My wife's father was the municipal president of Nacosari — Gustavo Torres. There's a bridge in Nacosari that has his name on it. He built it.

I feel that there aren't many journalists or people interested in knowing the truth about Murrieta. I want to make sure that people understand the message to the government and people of the United States. Our fight as the national association of descendants of Joaquin Murrieta is for a better understanding of who he was. It is very clear that he was not a bandit, or the "gringo killer".

He wanted to take back the part of Mexico that was stolen. Mexico was mutilated, and he wanted to recover part of it, because he loved his country. Look — now North Americans are fighting in Afghanistan, which is not their country, but they were hit hard with the horrible terrorist attack in New York. North Americans, if they had seen their country attacked, would have done the same thing that Joaquin Murrieta did at that time. The only thing Murrieta did was defend the people from Sonora that were living there, to protect themselves and their wives, to keep them from being stripped of their land and their earnings, so they wouldn't be forcibly obligated to work in the mines and agriculture.

We have to travel this path, because there are many Mexicans here now, and we have to understand each other better.

|

|

El Voludo, Sonora 12/5/02 A scarecrow on the fence next to a miner's home in El Voludo. Since there is no garden or plants to attract birds, this scarecrow is perhaps meant to scare people away instead. |

- Miners & Mayos

- Some Chicano History

- A Descendent of

Joaquin Murrieta - Three Miners

- Help from the North

- Miners' Union Officer

- A Blacklisted Miner

- A Striker's Story

- The Deer Dancer

- A High School Teacher

WORKPLACE | STRIKES | PORTRAITS | FARMWORKERS | UNIONS | STUDENTS

Special Project: TRANSNATIONAL WORKING COMMUNITIES

HOME | NEWS | STORIES | PHOTOGRAPHS | LINKS

photographs and stories by David Bacon © 1990-

website by DigIt Designs © 1999-